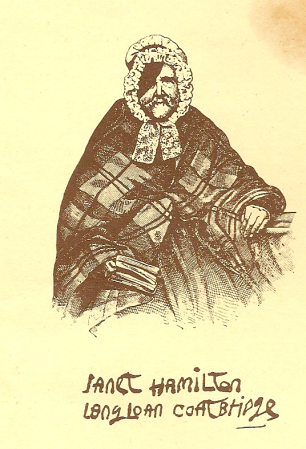

Janet Hamilton overcame the limitations of a working-class background to compose over two hundred and fifty poems. She was an avid reader from a young age, but only learned how to write when she was fifty years-old. Her favourite authors were Plutarch, Shakespeare, Milton, the Bible, Allan Ramsay, Robert Fergusson and Burns (McMillan, 84). Her husband John transcribed twenty of her poems during her late teens, but it was only in 1850 at the age of fifty-five that she made her first appearance in print (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 66-7). Partial blindness in 1855 developed into complete blindness by 1866, and her son James became her amanuensis (Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 52). Hamilton grapples with many working-class problems in her poetry and prose, but she encourages her peers to educate themselves and their children, drink less, use Scots, and recognize environmental change.

John Cassell, editor of the penny weekly The Working Man’s Friend, helped launch Hamilton’s literary career (Boos, “ The ‘Homely Muse’ ” 268-9). Cassell released the supplementary volume The Literature of Working-Men in 1850 to publish successful entries from an essay competition. Hamilton became the most frequent contributor with six essays (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 67). These include “Our National Curse” in August 1850 on alcoholism, “To the Working Women of Britain” in January 1851 on feminism, “The Mental Training of Children” in March 1851 on working-class education, and “Sketch of a Scottish Roadside Village Fifty Years Since” in July 1851 on village life. Hamilton also contributed two poems to the Working Man’s Friend: “The Wayside Well” in 1850 and “Summer Voices” in 1853 (Boos, “The ‘Homely Muse’ ” 282). Between 1853 and 1854, The Adviser – the Scottish Temperance League’s magazine for youth – published six of Hamilton’s temperance poems (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 70). In September 1860 Commonwealth published Hamilton’s “Rhymes for the Times – I” and in July 1863 Cassell’s The Quiver printed “Woman” and “Lines on the Calder” (Boos, “The ‘Homely Muse’ ” 282).

Hamilton publicly thanked and commemorated Cassell for his advancement of working-class literacy. In her preface to “The Wayside Well” she “express[es her] feelings of gratitude and respect for the unspeakable boon [Cassell] ha[s] bestowed on the working classes” through his publications (quoted in Boos, “The ‘Homely Muse’ ” 267). She also wrote the eulogistic poem “On the Death of John Cassell, The True and Esteemed Friend of the Working Man” for her third volume of poetry. In this poem she identifies Cassell as a “leader in the van of knowledge still” (Boos, “The ‘Homely Muse’ ” 268).

All of Hamilton’s volumes of poetry were printed in Glasgow. Publisher Thomas Murray printed Hamilton’s first two volumes of poetry: Poems and Essays of a Miscellaneous Character in 1863 and Poems of Purpose and Sketches in Prose in 1865, and James Maclehose published the final two: Poems and Ballads in 1868 and Poems, Essays, and Sketches in 1870 (WorldCat). Maclehose also released “memorial” editions of Hamilton’s last volume in 1880 and 1885 (Orlando). Most of Hamilton’s periodical poems reappear in her 1863 volume. In the preface to Poems of Purpose from 1865 she identifies a common theme in her writings: “[a] desire to hold at times sweet (some will say uncouth) converse with dear old Mother Scotland, before her native Doric, her simple manners and habits, are swept away by the encroaching tides of change and centralization” (quoted in Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 71). Hamilton dedicates Poems and Ballads to “her Brothers / The Men of the Working Classes.” She includes “sisters of the working-classes” in the preface to her next volume (quoted in Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 68).

Industrialization influenced many of Hamilton’s writings. Her local village of Langloan became engulfed by Coatbridge, which grew four times larger between 1821 and 1851 (Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 54). Her friend and biographer Joseph Wright commented that she often composed at night with “the thud of the ponderous hammers smashing the molten metal in the works close by [. . .] and the never-ending rattle of machinery” (quoted in Findlay, 368). She comments in her essay “Local Changes” that “the lover of nature has exchanged the whistle of the blackbird and the song of the thrush for the shrieking, hissing, and whistling of steam” (printed in Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 108). There is “Explodin’ an’ smashin’ an’ crashin’, an’ then / The wailin’ o’ women an’ groanin’ o’ men, / A’ scowther’t an’ mangle’t, sae painfu’ to see” (“A Wheen Aul’ Memories,” printed in Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 67). Industry replaces dwellings and people: “Noo the bodies are gane an’ their dwallin’s awa’ / An’ the place whaur they stood I scarce ken noo ava” (printed in Boos, Working-Class Women Poets, 68). “Luggie Past and Present” follows the transformation of River Luggie into a polluted waterway, and “Rhymes for the Times. IV.– 1865” describes how “bodies, like mowdies, by hunners an’ scores, / Are houkin’, an’ holin’, an’ blastin’ the rocks; / An’ droonin’s an’ burnin’s, explosions an’ shocks” (quoted in Findlay 372).

Amidst her many temperance essays and poems Hamilton wrote “Oor Location” and “Our Local Scenery” to address both industrial change and alcoholism. Her speaker in “Oor Location” notes that many men are “drucken randies . . . gaun for nouther bread nor butter, / Just to drink an’ rin the cutter.” She concludes that “Owre a’ kin’s o’ ruination, / Drink’s the kind in oor location” (quoted in Findlay 371). In “Our Local Scenery,” “It’s the drink, it’s the drink that licks up the siller” (quoted in Findlay 372). Florence Boos suggests that one of Hamilton’s sons was an abusive alcoholic, and thus temperance was of immediate concern (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 266).

In her didactic pieces Hamilton urges the working-classes to educate themselves and their children and include women in reform movements. In her essay “To The Working Women of Britain” she warns her peers of “the danger of your present incapacity to read” (printed in Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 102). At the time of publication one in four working-class women in Scotland was illiterate (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 63). Hamilton comments that male reformers and workers confront women with a “spirit of predominance and exclusiveness.” She calls on them to “includ[e] the females of your class . . . in every movement for furthering the intellectual advancement of your order” (Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 102-3). In “A Lay of the Tambour Frame” the speaker points out to male workers that “She who tambours . . . Would have shoes on her feet, and dress for church, / Had she a third of your pay” (ll. 37-40). In “Rhymes for the Times – I,” Hamilton’s speaker questions the manhood of those who “hae nae time for e’enin classes; / Ye’ve time to drink, an’ see the lasses” (ll. 29-30). She knows that “Had ye the wull, wi’ book an’ pen / Ye’d fin’ the way to mak’ ye men” (ll. 37-8).

Hamilton supported political movements outside of Britain and wrote pacifist and anti-slavery poems. She supports Polish Independence in the poem “Poland” and Italian Unification in the poem “Freedom for Italy – 1867.” Hamilton even donated her son’s gift of a gold nugget to Italian General Garibaldi (Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 52). She also wrote many poems against the Crimean War and the American Civil War (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 73).

As her career progressed, Hamilton defended and used more Scots in her poetry (Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 52). She satirizes those “big men o’ print / To Lunnon ha’e gane, to be nearer the mint” in “A Plea for the Doric.” She laments the influence of this English printing culture, where “Doric is banish’d frae sang, tale, and letter” (quoted in Findlay 373). Similarly, Hamilton’s speaker in “Auld Mither Scotland” exposes how “It’s England’s meteor flag that burns / Abune oor battle plains . . . It’s England aye that gains.” The speaker laments the death of Scots: “oh! I fear the Doric’s gaun . . . There’s mony noo that canna read / Their printit mither tongue” (printed in Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 80).

Hamilton received positive reviews from at least forty-six journals in Britain and elsewhere (Boos, “The ‘Homely Muse’ ” 263). She established herself among readers of The Airdre and Coatbridge Advertiser, and reviewers with The Christian News, United Presbyterian Magazine, Evangelical Repository, and League Record also enjoyed her work (Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 68). Even larger periodicals such as Pall Mall Gazette, St. James Gazette, and Punch offered praise. In June 1863 The Athenaeum named Poems and Essays of a Miscellaneous Character “one of the most remarkable [volumes] that has fallen into our hands for a long time past. It is a book that ennobles life, and enriches our common humanity” (quoted in Boos, “Janet Hamilton” 64). The Glasgow Herald gave her a glowing review on 28 November 1868: “The name of Janet Hamilton is one of the most remarkable in the history of Scottish poetry” (Boos, Working-Class Women Poets 53).

Hamilton addresses contemporary issues in her writings such as urbanization, industrialization, alcoholism, illiteracy, political turmoil, and the colonizing influence of English. Some contemporary and modern critics found Hamilton’s writings to be too conservative or too invested in pastoral myth. According to William Findlay, much contemporary criticism in the nineteenth century held that Scottish literature avoided the reality of industrialization and social change. Both Hamilton in “A Plea for the Doric” and Findlay contend that Anglocentrism informs this view (373). Modern scholar Brian Maidment considers Hamilton’s writings to be “a compendium of ferociously conservative attitudes,” but the social problems in Hamilton’s writings directly impacted her life and the lives of her contemporaries (cited in Boos, Companion 70).

Works Cited

- Boos, Florence S. “Janet Hamilton: Working-class Memoirist and Commentator.” The Edinburgh Companion to Scottish Women’s Writing. Ed. by Glenda Norquay. Edinburgh UP, 2012.

- Boos, Florence S. “The ‘Homely Muse’ in Her Diurnal Setting: The Periodical Poems of ‘Marie,’ Janet Hamilton, and Fanny Forrester.” Victorian Poetry 39.2 (Summer 2001): 255-86.

- Boos, Florence S. Working-Class Women Poets in Victorian Britain: An Anthology. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2008.

- Findlay, William. “Reclaiming Local Literature: William Thom and Janet Hamilton.” The History of Scottish Literature (v.3). Edited by Douglas Gifford. Aberdeen UP, 1988.

- Hamilton, Janet. “A Lay of the Tambour Frame.” Poems and Ballads. Literature Online. 20 February 2013. Web.

- Hamilton, Janet. Poems and Essays of a Miscellaneous Character; Poems of Purpose and Sketches in Prose; Poems and Ballads; Poems, Essays, and Sketches. Bibliographical records in WorldCat.

- Hamilton, Janet. “Rhymes for the Times – I.” Poems and Essays of a Miscellaneous Character. Literature Online. 20 February 2013. Web.

- “Janet Hamilton.” Orlando: Women’s Writing in the British Isles from the Beginnings to the Present. Ed. Susan Brown, Patricia Clements, and Isobel Grundy. Cambridge UP Online, 2006. 23 January 2013. Web.

- MacMillan, Dorothy. “Janet Hamilton (1795-1873).” A History of Scottish Women’s Writing. Ed. Douglas Gifford and Dorothy McMillan. Edinburgh UP, 1997.

Further Resources

- Bold, Valentina. “Beyond ‘The Empire of the Gentle Heart.’ ” A History of Scottish Women’s Writing. Ed. by Douglas Gifford and Dorothy McMillan.” Edinburgh UP, 1997.

- Boos, Florence S. “Hamilton, Janet (1795-1873).” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford UP, 2004. 20 February 2013. Web

- Morgan, Edwin. “Scottish Poetry in the Nineteenth Century.” The History of Scottish Literature (v.3). Edited Douglas Gifford. Aberdeen UP, 1988.

Thomas S.